If you’ve ever downloaded Linux updates or tried installing a distribution like Ubuntu, you may have seen the word “mirror” pop up. It sounds technical, but the idea is surprisingly simple.

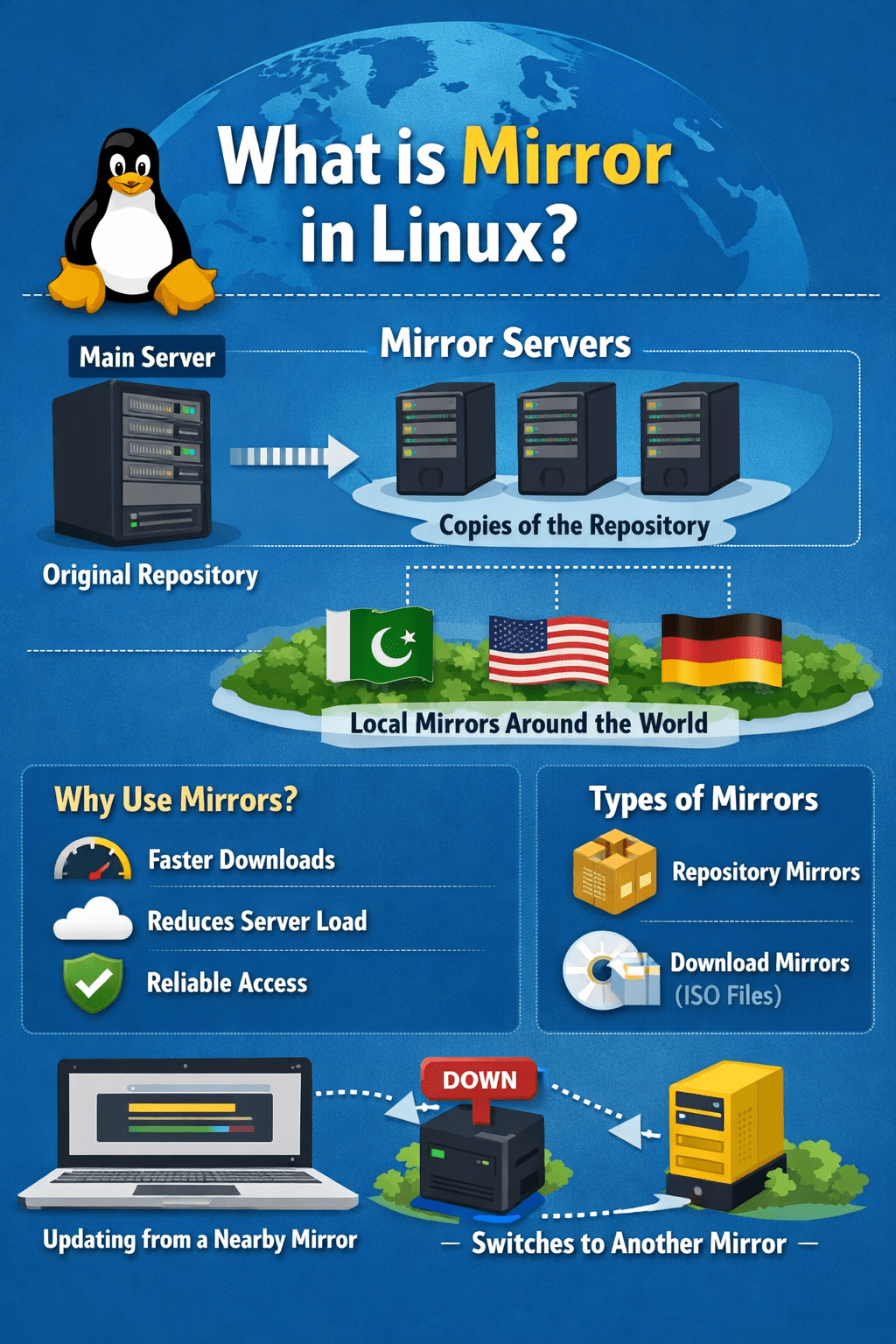

In Linux, a mirror is basically a copy of software or data that’s stored on another server. Think of it like a backup store that carries the exact same products as the main store. If one store is too crowded or far away, you just go to another location that has the same items.

That’s exactly how mirrors work in Linux.

Why Does Linux Need Mirrors?

Linux distributions such as Ubuntu, Fedora, or Debian maintain huge collections of software packages. These packages include everything from web browsers and office tools to system updates and security patches.

Now imagine millions of users around the world trying to download updates from just one central server. It would slow down dramatically — or even crash.

So instead, the main server creates copies of its repository (the big storage place where software packages live) and distributes them to many different servers around the world. These copies are called mirrors.

When you run a command like:

sudo apt updateyour system connects to one of these mirrors to check for new updates. It doesn’t usually contact the original central server. That’s like buying groceries from your local branch instead of flying to the company’s headquarters.

A Simple Real-World Example

Let’s say you want to download a large Linux ISO file (the installation file). If everyone worldwide downloaded it from one server in, say, the United States, users in Asia or Europe would experience slow speeds.

Instead, Linux provides mirrors in many countries. If you’re in Pakistan, your system will likely choose a mirror closer to you, giving you faster download speeds.

It’s similar to how Netflix uses servers around the world so your movie doesn’t buffer. The content is the same — just stored in multiple places for efficiency.

Types of Mirrors in Linux

There are generally two common types of mirrors:

1. Repository Mirrors

These store software packages and updates. Your package manager (like apt, dnf, or yum) pulls updates from these mirrors.

For example:

- Ubuntu repository mirrors

- Debian repository mirrors

- Fedora repository mirrors

They all contain the same official packages — just located in different geographic locations.

2. Download Mirrors

These host downloadable files like ISO images. When you visit a Linux distribution’s website and see a list of download servers by country, you’re choosing a mirror.

The file you download is identical no matter which mirror you choose.

How Does Linux Choose a Mirror?

Sometimes you choose manually. Other times, your system selects automatically based on:

- Geographic location

- Server speed

- Availability

Some distributions even test mirror speeds and automatically pick the fastest one for you.

It’s like Google Maps choosing the fastest route for your commute.

Are Mirrors Safe?

Yes — as long as they are official mirrors. Linux distributions verify packages using digital signatures (a kind of electronic fingerprint). If a file is altered or tampered with, your system will detect it.

So even though you’re downloading from a mirror, your system still checks to ensure the software is authentic and secure.

What Happens If a Mirror Goes Down?

No problem. That’s the beauty of mirrors.

If one mirror is unavailable, your system can switch to another. It’s like having multiple ATMs — if one isn’t working, you simply try the next one.

This redundancy (having backups) makes Linux updates reliable and globally accessible.

Key Takeaways

A mirror in Linux is simply a replicated copy of software repositories or files hosted on different servers. Its purpose is to:

- Improve download speed

- Reduce load on the main server

- Provide reliability and backup

- Make software accessible worldwide

So next time you update your system or download a Linux distribution, remember — you’re not connecting to one magical super-server. You’re using a smart global network of mirrors designed to make your experience fast and smooth.

Technology can seem complicated, but often it’s built on simple ideas — like putting multiple copies of the same book in different libraries so everyone can read without waiting.

Check out my collection of e-books for deeper insights into these topics: Shafaat Ali on Apple Books.

Leave a comment